By Stella Uiterwaal, Biodiversity Postdoctoral Fellow

Since I was a kid, I’ve always liked animals. Growing up, I had a pet rabbit and chickens. My parents let me fill tanks with tadpoles and little fish. I fed parsley to swallowtail caterpillars and waited not-so-patiently for them to transform into butterflies.

At some point in middle school, I decided I wanted to be a veterinarian. Then I wanted to be an astrobiologist. Finally, I landed on ecology. My younger self would be so excited to know I made that dream a reality. Today, I am a postdoctoral researcher for the Forest Park Living Lab where I continue to marvel at the natural world through science, asking questions and collecting data to find the answers.

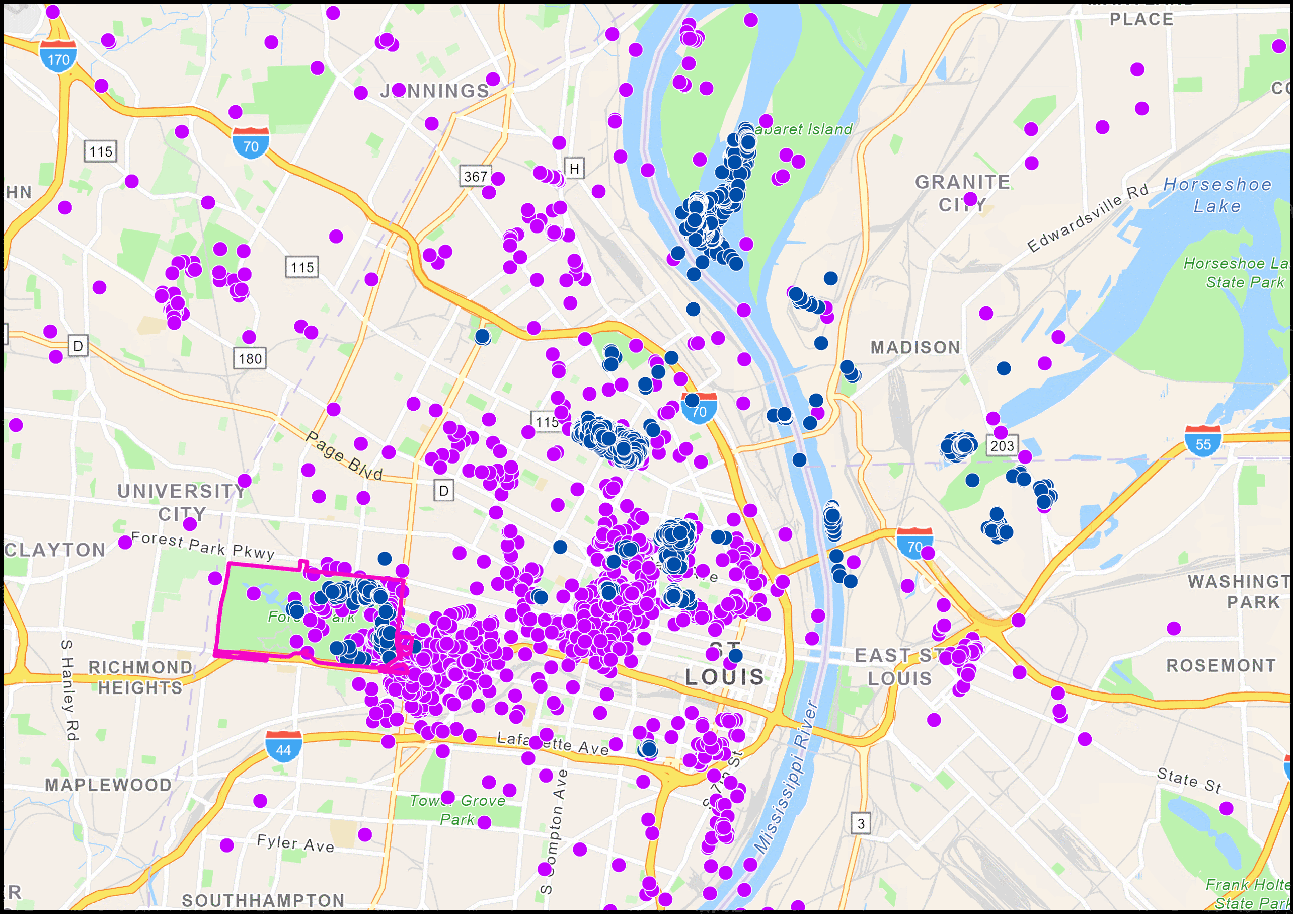

Forest Park Living Lab is a collaborative effort between several St. Louis area institutions, including the Saint Louis Zoo Institute for Conservation Medicine (ICM). Our goal is to understand the health, ecology and movement of wildlife in Forest Park, a 1,300-acre jewel of a park that is also home to the Zoo. The project is aimed at fitting many wildlife species with tracking tags that collect data showing how these animals use habitats in the park, including lakes, golf courses and restored woodlands and prairies. We also collect wildlife health data, gathering samples to test for diseases and animals’ overall health. We are targeting a wide range of species: anything from reptiles to mammals to birds. Such an ambitious project requires a lot of work and expertise.

Studying Forest Park’s Wildlife

So how do we do it? The first step is basic natural history and field ecology. We confirm which species are in the park and observe where and when they are likely to be found. Sometimes we travel around the park — on foot, by bike or in a car — to document species of interest. We also use motion-triggered camera traps that take time-stamped photos of animals walking by. These cameras are an important tool because they give us information about secretive animals that avoid humans and work in the middle of the night when we are asleep! The third way we learn about animals’ habits is from Forest Park visitors. We always appreciate information on wildlife sightings submitted to our website!

Next, we start planning how to trap a few animals from each species to fit them with tracking tags. The team has a lot of experience with capturing all sorts of wildlife, but if a species is new to us, we consult with local experts. Some animals, like box turtles, can be captured without much planning. Others, like coyotes, require months of preparation and coordination.

We always prioritize safety. This means we make sure the capture method is appropriate for the species and our urban environment, the weather conditions are just right and the team has a plan. We also get our plans approved by the Zoo and obtain local, state and federal permits (depending on the species). Throughout the process, we work closely with Forest Park Forever to make sure everyone is on board.

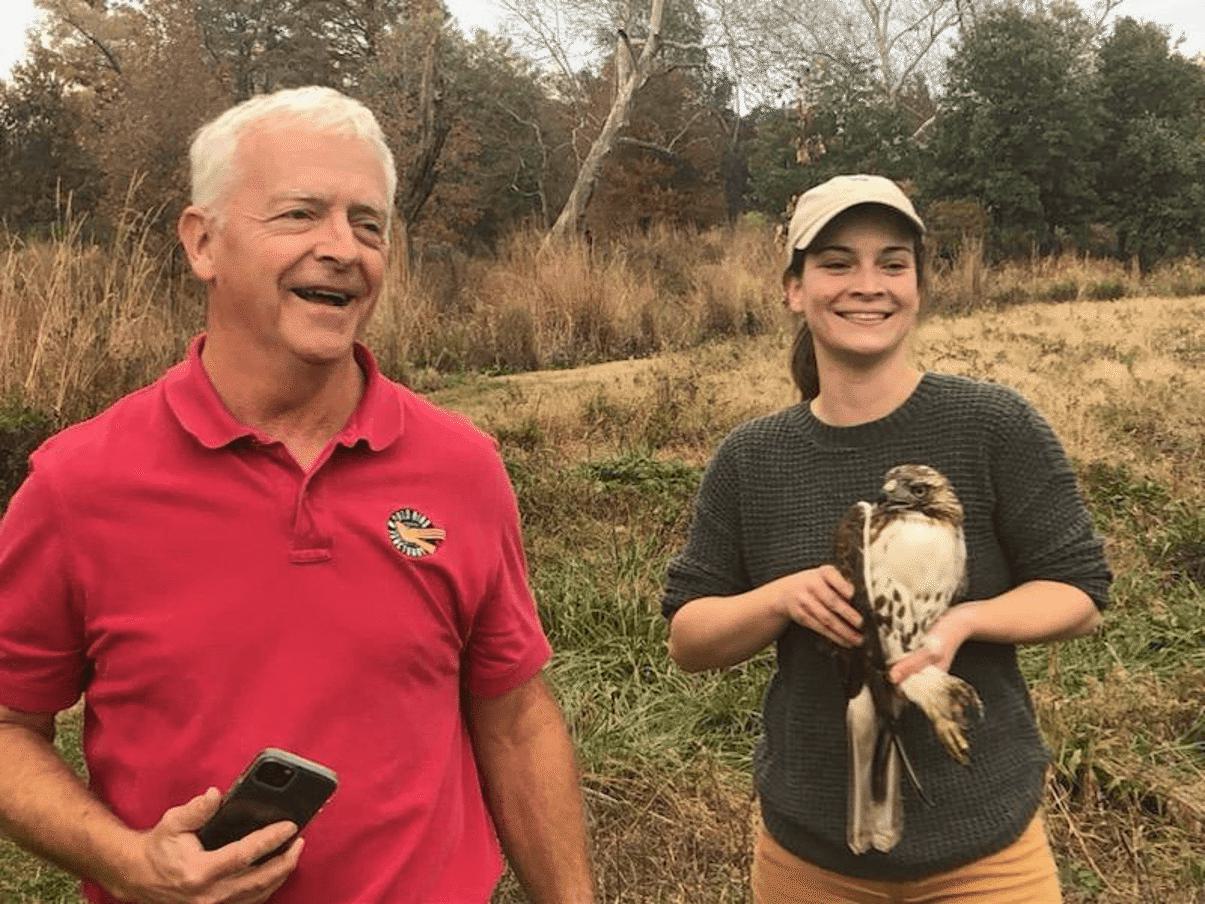

When everything is in place, the tagging begins! Sometimes this means long nights waiting for a coyote that never shows up, driving around the park to look for hawks that have magically disappeared or arriving at a trap before dawn to see that no one visited overnight. Other times, we are successful! The successful capture of an animal is cause for celebration, but it also means the pressure is on. Our job is to collect health information, attach a tracking device and release the animal as quickly and as safely as possible. We use eye covers to help keep animals more comfortable. Some animals, like raccoons, are placed under anesthesia during the process. Veterinary experts, including Dr. Sharon Deem and Jamie Palmer from ICM, take the lead on anesthetic protocols, performing physical examinations to determine overall health and collecting samples to use for further analysis.

Once the collection of health data is complete, we attach the tracking tag. Firstly, we make sure the tag is not too heavy and attached comfortably to the animal. Research has shown that staying under 3% of an animal’s body weight is best. Most of the tags weigh just a few grams! Mammals wear their tags on collars, birds wear small backpacks that hold the tag on their upper back and turtle tags are attached to the carapace — their upper shell — with non-toxic epoxy. Whatever attachment method we choose, we want to make sure it won’t interfere with the animal’s everyday life, including behaviors like foraging, preening and mating.

For daytime animals that spend time out in the open, we can use tags that are charged by little solar panels.

The last step is to release the animal. Many of our large tags upload data directly once a day to Movebank, a large repository of animal movement data. The first 24 hours after the release are so tantalizing! I am always on the edge of my seat waiting to confirm that the tag is working and to see where the animal goes. Over time, the data builds up and we learn all about the animal’s habitats, when the animal is active and how human activities influence the animal’s movement. Repeated over many different animals and species, we are developing a uniquely integrative understanding of Forest Park’s wildlife.

For me, the capture and release steps are the most exciting. It is so special to be up close and personal with Missouri’s native wildlife and get unique glimpses into the lives of non-human St. Louisans. I feel privileged to have our lives intersect for a few short moments and to get to know these animals so well through the wealth of data they provide for us.

So much to learn!

Postdoctoral positions are temporary by design, but this does feel a lot like a dream job. Where else can you follow your curiosity, spend time with animals and contribute to conservation efforts? Each day on the job is different, and I also get plenty of opportunities to share my sense of wonder with kids and students.

The Forest Park Living Lab is more than a collaboration of institutions. It’s a group of highly passionate conservationists, veterinarians, ecologists, educators and students all working together to understand and protect the wild beauty in Forest Park. Our native wildlife faces so many daily existential threats. Some, like diseases and parasites, may be natural. Many, however, are caused directly by humans such as being hit by cars or being taken into captivity from the wild. Understanding wildlife health and its connections to human health and environmental health—known as One Health— is so important for our future and the future of our planet.

I hope and encourage others to give our local wildlife a closer look. Lions and penguins are cool, but there is just as much to learn about the creatures in your backyard and our neighborhood park. I hope next time you are out in Forest Park, you take a moment to marvel at the beautiful complexity of the natural world around you.