Author: Director of the Saint Louis Zoo Institute for Conservation Medicine Sharon Deem

When the 2022 World Wildlife Fund Living Planet Report was published I was in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, having just returned from a river dolphin rescue mission in this South American country of contrasting beauty. Reading the report on the heels of my days and nights of “chasing” river dolphins amplified the crisis at hand. I noticed the pictures in the report showed the same challenges that my team and I had just witnessed. We were living the report!

The conservation costs of the growing human footprint, as spelled out in the Living Planet Report, was what brought me to Bolivia on a field mission in October 2022. I was there as a member of a team of dedicated biologists, veterinarians, and fire fighters (yes, fire fighters!), to rescue two endemic river dolphins, Inia boliviensis, confined to a human-made artificial canal. Artificial canals and lagoons are expanding in the region due to increased food production. With the growing human population around the world, the demand and need for more food also grows.

Now as I sit back in my office at the Saint Louis Zoo and reflect on my travels in Bolivia, I ponder the challenges, and the solutions, for wildlife conservation, environmental sustainability, and human health — the holistic approach known as One Health.

Moving a River Dolphin from Point A to Point B

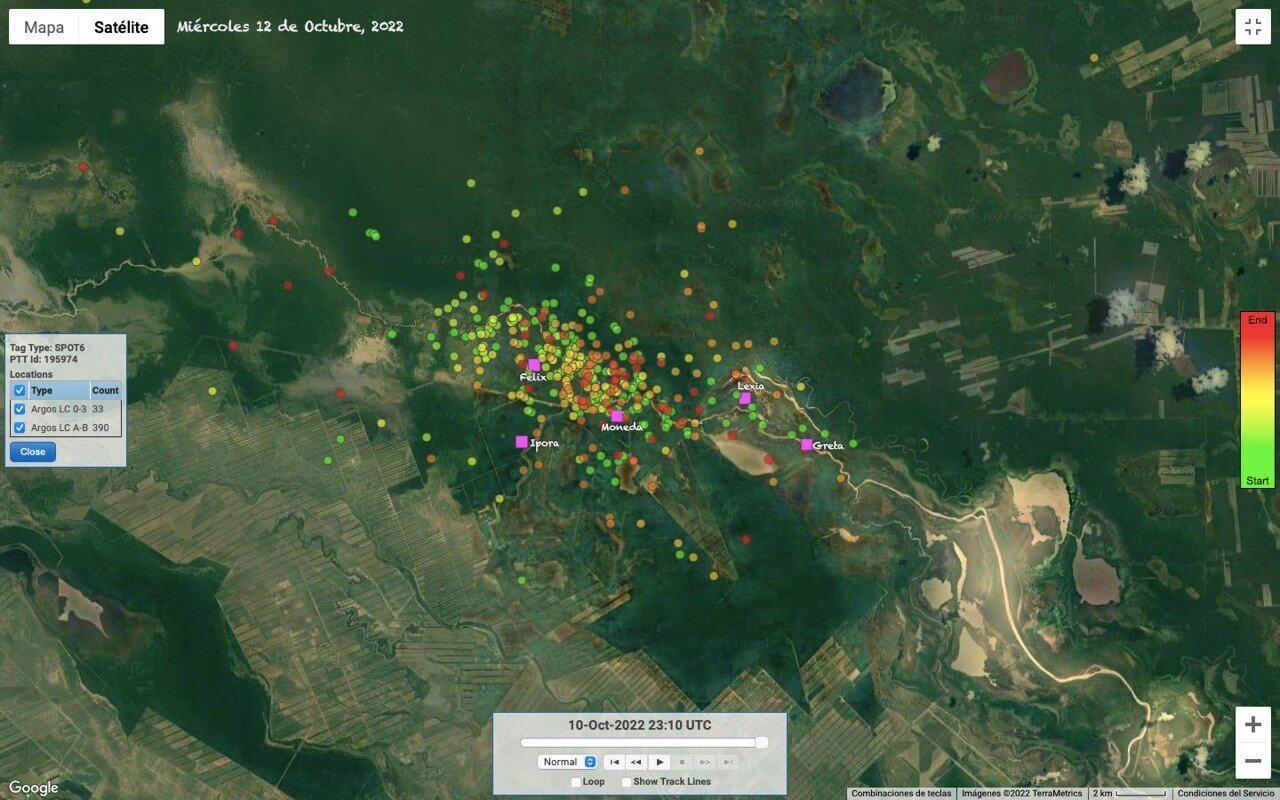

With a team of 15 experts, many members having years of dolphin rescue experience, much of our work went smoothly. The scouting of the site had occurred in September, and we knew where the dolphins would be found and the necessary infrastructure we would need—nets, portable pools, transport stretchers, boat and truck vehicles, and veterinary supplies, which I would bring to perform full health assessments. Lastly, we had telemetry tags, which would be placed on the dolphins before translocating them back into a free flowing river. This important part of the mission allows us to follow the dolphins’ movements still today and in the coming months.

I am happy to report that Lexia (named for lead fire fighter Alex) and Moneda (named for the area where we worked, La Moneda (the coin)) were safely moved from a shallow artificial canal and back into the Rio Grande (the big river). The work involved wading in chest deep water to install rope barriers so we could then move the dolphins into these areas and carefully lift them from the water onto our boat. Both Lexia and Moneda did well in the transition, including during the health evaluation, tag placement, truck transportation, and release. Thankfully, we still continue to get signals from the tags weeks after the rescue, and based on the movement data, I imagine the dolphins are both happy now that they are back in the fast-flowing, muddy river water they call home.

But, Why Move a River Dolphin?

Similar to other freshwater river dolphin species, threats to I. boliviensis survival include anthropogenic (human originated) changes that directly impact river health. These human-driven changes come from the construction of dams and the channeling of rivers; agricultural and livestock runoff; overfishing; pollution; and human encroachment into river watersheds that, until recent decades, were pristine. All of these threats have negative impacts on the health of aquatic species, including river dolphins.

With these land modifications, river dolphins like Lexia and Moneda often become trapped in artificial water bodies that form during the rainy season. When the dry season arrives, many of these artificial canals and lagoons disappear. As they dry up the dolphins can no longer survive, and yet they also have no way to swim back to their river home. That is when this group of dedicated conservationists, literally, come to the rescue. By moving trapped dolphins from shallow water bodies and taking them to healthy rivers in the region, the dolphins have a second chance for survival. With fewer than 500 Bolivian river dolphins remaining today, our work is crucial. We know that the life of every dolphin matters!

Solutions for Today’s Conservation Challenges

Lexia and Moneda are only two of 59 river dolphins successfully rescued by the Saint Louis Zoo’s Bolivian colleagues over the last 12 years. During the October field mission, both dolphins were given veterinary health assessments. We have now performed complete health evaluations of 15 dolphins including these 2 and 13 others from previous team missions. Every rescue mission offers a second chance of survival for the individual dolphins and, perhaps more importantly, hope for a species endangered with extinction. However, these missions can feel a bit like placing a small band aid on a very large wound. Wouldn’t it make more sense if we could keep dolphins from getting trapped in these artificial water bodies rather than trying to move them back out to the river? We should consider measures to prevent the entrapment of these animals in the first place.

When thinking about this trip and the Living Planet Report, as well as the historical milestone we reached on November 14, with 8 billion humans alive today, I reflect on how each of us influences planetary health, including freshwater dolphins that live in the rivers of South America. These issues may feel far away from us, but they are directly connected to our actions. We all are responsible for the speed and scope of changes across the globe. For example, consider our consumption of natural resources. The foods we consume, from local to global, along with their associated carbon costs must be factored into our individual planetary footprints. How will we feed 8 billion humans without irreversibly impacting the other species that share Earth with us? What measures can we take to produce the foods and clothing and other resources that make it possible for humans to lead healthy lives?

A phrase that often came up during our team discussions on conservation was “necesitamos esperanza.” We need hope! But we should add to this phrase: “necesitamos esperanza y acción.” We need hope and action! The fire fighters on our team have hope and they take actions, using their skills honed from years of environmental and human rescue experiences to help their biologists and veterinary colleagues save the endemic river dolphin of their country. There is great hope with teams of caring people, such as our team in Bolivia, taking actions and working globally to mitigate the negative impacts we humans may have on biodiversity.

Today is the day we each should ask, “What is a Dolphin’s Life Worth?” and “What actions will I start right this minute that help support wildlife conservation, environmental sustainability, and human health?” The list is endless and there is much each of us can do to ensure One Health. Today is the right day to start.

Additional Information

- Read a blog post from the August mission by Dr. Ellen Bronson of the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore.

- Funding for this work comes from the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians Wild Animal Health Fund. Learn more.

- Did you know? The local word for river dolphin in Bolivia is bufeo!